Acadia Tucker adding compost and mulch to permanently raised beds.

By Acadia Tucker

Acadia is a carbon farmer and gardener, and author of Growing Good Food: A Citizen’s Guide to Backyard Carbon Farming. Acadia is one of 200+ farmers and food system professionals who will be leading sessions at our 2020 Sustainable Agriculture Conference, happening February 5–8 in Lancaster.

Update: Due to unforeseen circumstances, Acadia is no longer able to speak at our 2020 Conference.

The Earth’s climate is changing faster during our lifetimes than it has at any other point in history. This is indisputable thanks to research done by climate scientists who have worked for decades to give us data we can use to both mitigate the damage, and prepare ourselves for what’s to come.

The last few years have seen record-breaking weather extremes around the world; in the U.S., these have included long, intense heat waves in the South, drought and flooding in the Midwest, and increasingly frequent and severe storms in the North. Climate change will continue to make the flooding, droughts, and other extreme weather even worse, putting an immense strain on crop production and resulting in massive global food shortages. A half billion people live in places that are already turning into desert, and the planet is losing soil between 10 and 100 times faster than it is forming.

“A half billion people live in places that are already turning into desert, and the planet is losing soil between 10 and 100 times faster than it is forming.”

Working as a farmer has given me an intimate view of how the climate crisis is shaping our world. When I first started to farm in Washington, my location at the northernmost tip of the state meant we had more than 15 hours of sunlight a day at the height of summer. For three years I watched as the summer sun cooked the soil during long periods of unprecedented drought. When it finally did rain, it was torrential and came all at once. Water pooled on the hard, packed dirt and dried up before it could percolate to where my plants needed it most. At some point, I started to realize these weather extremes were not just a blip but a pattern.

Alarmed, I went back to school to study soil management and how it can be a meaningful buffer against weather extremes. When I returned to farming, I started covering my fields every spring with a generous layer of compost. Then I’d lay down another protective layer, this time of straw or wood chips, to keep the compost from washing away and prevent new weeds from sprouting. When it came time to plant, I gave up tilling and instead relied on permanent raised beds in the fields so that the soil remained undisturbed.

In small-scale, no-till systems, a broadfork is a handy tool for loosening raised beds without significantly disturbing the soil.

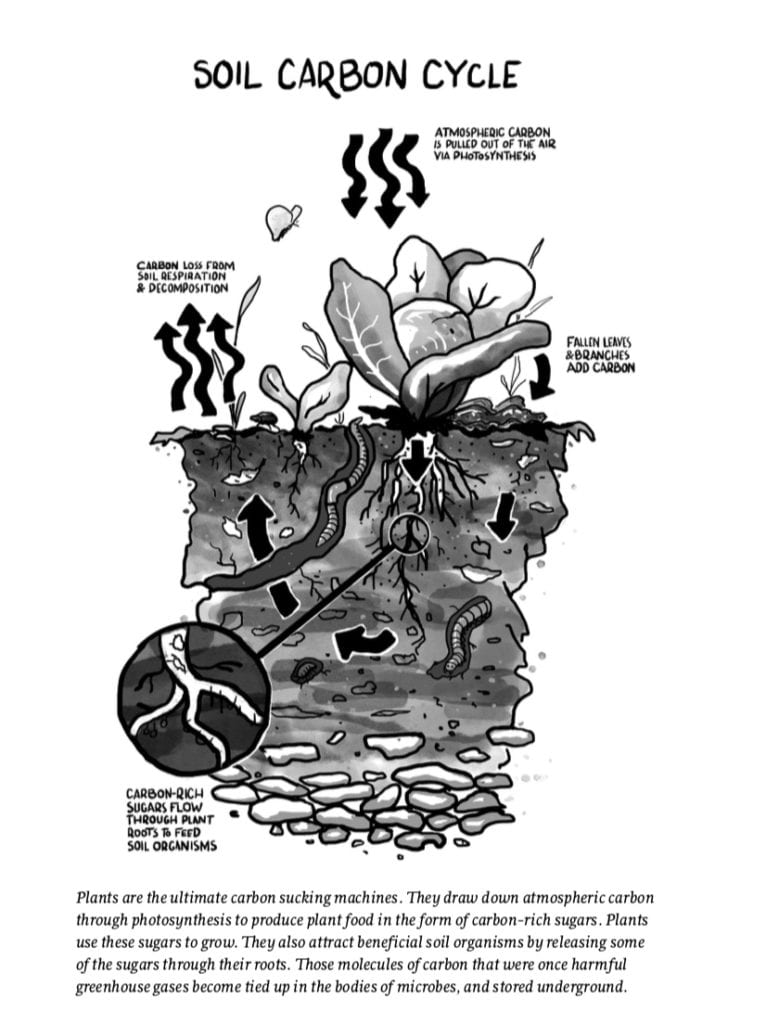

I quickly realized that soil, if treated right, helps to buffer plants from the effects of the extreme weather caused by our warming world. I observed that my healthy soil held more water, resisted erosion, and warmed more quickly in the spring. But the most important benefit of caring for my soil was the ecosystem of soil organisms I was supporting—the very organisms that recycle nutrients, ward off pests, naturally aerate the soil, and help carbon stay out of the atmosphere. This ability to capture greenhouse gases is why many experts believe carbon farming could play an important role in fighting climate change.

For me, learning more about the soil’s ability to heal the Earth was life changing. By the time I finished graduate school, I’d decided to grow food in a way that promotes building organic matter, which is the essence of regenerative, or carbon, farming. Regenerative practices expand upon the soil’s already impressive storage capacity: Our natural landscapes absorb 29 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions.

Changing the way we grow food could buy us more time. And it all starts by caring for the soil. It is an amazing truth, one that requires major changes in the way farming is practiced.

“Changing the way we grow food could buy us more time. And it all starts by caring for the soil.”

Planting a single crop over vast amounts of acreage, leaving the soil bare for long periods, and relying on frequent plowing accelerates the loss of healthy topsoil, releases buried carbon into the air, and uses too much water. Poor soil weakens plants and makes them more vulnerable to pests and disease. This necessitates higher levels of chemical fertilizers and pesticides that, in turn, kill the beneficial organisms in the soil that feed plants and help make the soil rich in carbon.

Credit: Joe Wirtheim

Farmed soils around the world have lost between 50 and 70 percent of their original carbon stocks, according to a recent study from the Carbon Management and Sequestration Center at Ohio State University. Most of that has ended up in the atmosphere. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that farms in this country released nearly 300 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent through poor soil management practices in 2016 alone.

While agriculture is a part of the problem, it has a miraculous ability to be a part of the solution. By adopting regenerative practices, farms could remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere at a rate of about one ton of carbon dioxide for every acre, according to data reviewed by soil expert Eric Toensmeier. The potential benefits are remarkable, as spelled out in a 2008 study from The University of Aberdeen in Scotland, which concluded that approximately 11 percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions could be offset by soil carbon sequestration if we start growing food this way. The authors write: “Through improved resilience to both floods and droughts, soil carbon sequestration, and all the other innumerable benefits of thriving soils, it’s clear that soil health must be at the center of any serious effort to farm sustainably in a changing climate.” Experts agree more study is needed to understand the full potential of carbon farming, but there’s no question that even a small increase in soil carbon can improve crop resilience, reduce chemical use, conserve water on a large scale, and draw down atmospheric carbon.

While fewer and fewer people are farmers by profession, many Americans are growing food. In fact, 35 percent of us, or 42 million households, report growing some of our own food, according to the National Gardening Association of America. Just imagine what could happen if more of us encouraged our friends and family to start growing good food. Not only would we have ready access to nutritious, local food. We could help heal the planet.

Acadia Tucker’s book Growing Good Food: A Citizen’s Guide to Backyard Carbon Farming invites us to think of gardening as civic action and offers plans for growers who have a little ground or a lot to steward Climate Victory Gardens. She offers advice on how to prep soil, plant food, and raise fruits, herbs, and vegetables using regenerative methods. She describes the climate changes taking place in our own backyards, and the many steps we can take to boost a garden’s resilience.

Growing Good Food also includes calls to action and insights from leaders in the regenerative movement, including David Montgomery, Anne Biklé, Gabe Brown, Wendell Berry and Mary Berry, and Tim LaSalle.