The 2018 Farm Bill expired over six months ago, and the next one is still many conversations away. What’s the hold up?

According to a report by the American Enterprise Institute, the largest 10% of farms receive 65.4% of all crop insurance subsidies.

Part of the issue is that Congress has not allocated any new money to the Farm Bill, so any increased spending in one Farm Bill title (such as commodity payments) means decreased spending in other areas (conservation or nutrition, for instance).

One of the principal fault lines facing members of Congress is the tension between increased spending on the farm safety net—a group of US Department of Agriculture (USDA) programs that offer risk mitigation and financial support to US farmers experiencing hardship caused by natural disasters, poor growing conditions, and/or market volatility (including crop insurance and commodity supports)—and preserving the Inflation Reduction Act’s historic investment in conservation.

And that funding dispute doesn’t take into account all the great new ideas clamoring for inclusion in the next Farm Bill, including programs around land access, local food procurement, and perennial systems. If we want to see those programs implemented, the money would need to come from somewhere; limiting government payments to large-scale, conventional producers is one pathway toward finding those dollars, but it is not a solution embraced by all parties and all stakeholders.

While the farm safety net is critical to our agricultural system, it is far from perfect. The crop insurance and commodity programs pick winners and losers, disincentivize conservation practices, and demand a high price tag (more than $142 billion between 2017 and 2022) that cannot be sustained.

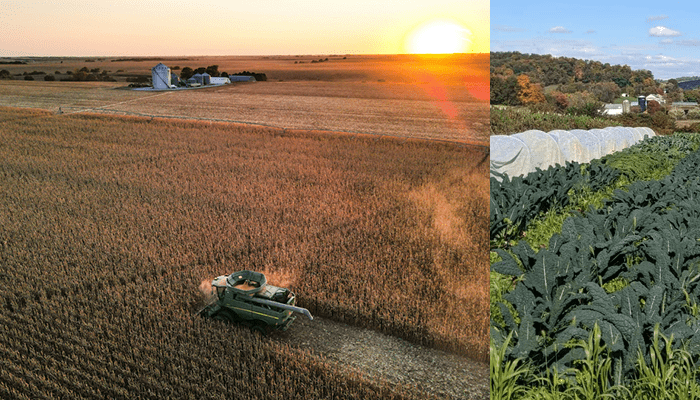

What’s more, these programs subsidize risky forms of commodity production—systems that are based on annual monoculture crops, overly reliant on off-farm chemical inputs, and chronically overuse tillage.

The 2022 Census of Agriculture revealed a trend toward farm consolidation and an alarming loss of 145,000 farmers. The continued concentration of resources in industrial farms is only likely to exacerbate this trend, but the correlation is rarely discussed on Capitol Hill.

Instead, members of Congress only hear about the important role that the farm safety net plays in helping farmers recover from disaster and revenue loss. However, these programs are primarily available only to a modicum of farms—mostly large, industrial commodity operations—and exclude most small- to mid-sized diversified farms.

According to Unsustainable: State of the Farm Safety Net, a report recently published by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC),

“Farm economists find that the largest 10% of farms with the highest annual crop sales nationally receive 65.4% of all crop insurance subsidies, and that the smallest 80% of farms receive just 23.3% of premium subsidies.

National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC)

It likely won’t surprise anyone to learn that many farmers within Pasa’s community haven’t found a crop insurance product that works well for them. For the most part, crop insurance is not designed for small or medium-sized diversified farms that grow food and fiber for their local communities.

Only 13% of U.S. farms were protected by a crop insurance plan in 2022.

According to an analysis by USDA Economic Research Service.

Rather, crop insurance was built for large commodity-crop farms that grow products like corn, soy, and wheat in mass quantities, which are often heavily processed before they make it to our plates—if they ever make it to our plates. (Many of these crops never enter the food system and are instead turned into products like ethanol.)

This means that while many small and medium-sized diversified operations are doing everything they can to farm in ecologically responsible ways—when climate catastrophe strikes, these are the farms left without a safety net.

The NSAC report showed similar findings:

NSAC

“In theory, crop insurance extends a safety net to all remaining farmers. In practice, it does not. The Congressional Research Service reported that only 20% of farms were insured in 2019, yet that 20% accounted for more than 90% of acres planted to corn, soybeans, and cotton and 85% of wheat acres.

More recently, a new analysis published by the USDA Economic Research Service found that just 13 % of U.S. farms were protected by a crop insurance plan in 2022. In 2023, farmers in Kansas, Texas, North Dakota, Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska—among the largest producers of row crops—enrolled most in the federal crop insurance program.”

Expanding the definition of the farm safety net allows us to think more holistically about how the Farm Bill can give farmers what they need to weather the storm.

Like most farms that benefit from crop insurance, the groups advocating for higher subsidies are large, well-funded, and well-connected. Convincing Congress to rethink the farm safety net status quo is an uphill battle, and they won’t address this problem without farmer input.

We need your stories to help legislators understand:

Call your members of Congress and tell them that the next Farm Bill should invest in climate resilience, equitable food systems, and farm viability—not continue to prop up a flawed and unsustainable system.

Want to share your story? Reach out to policy@pasafarming.org to get involved!

Learn more:

Here are a couple of resources that I found useful in deepening my understanding of this issue: