Rotational grazing and organic management have helped Rocky Hollow Dairy prioritize the health of their herd and land. As the changing climate and fluctuating markets present new challenges, they’re finding creative ways to adapt and investing in climate-smart practices like silvopasture to grow long-term solutions.

The Hertzler family has been in the dairy business since the 1970s. They adopted a rotational grazing system in 1994, and today the 250 cows at Rock Hollow Dairy are 100% grass-fed and their operation maintains a USDA Organic certification. Farmer Neil Hertzler says these management strategies, along with careful monitoring, have helped their cows live longer, more productive lives and improved the overall health of the herd.

Rather than buying premium organic feed, the Hertzlers focus on maintaining more than 350 acres of rolling pastures in Perry County, Pennsylvania. These grassy hills provide the high quality forage that fuels Rock Hollow’s milk and cheese production, which has maintained organic certification since 2017.

Each year, the cows are sent out to graze in early April—or sooner if there’s a mild winter—and will typically spend their days on pasture until mid-November. But what happens when it’s so hot that the cows prefer to return to the barn rather than staying out to graze?

While the Hertzlers can recall past years when the grass in the pasture turned yellow and the high temperatures were difficult to manage, the heat waves and lack of rain in the summer of 2024 were particularly noticeable at the dairy.

During recent heat waves, it’s not uncommon that cows will opt to leave the pasture and return to the barn by mid-morning, preferring the readily available hay, shelter from the sun, and cooling fans.

The hay in the barn is intended to be saved for winter when the grazing season is over, but the cows have been eating into these winter stores during the summer, when the cool barn is more appealing than the dry, sunny pasture.

As climate change impacts are felt on farms across the Eastern US, integrating management practices that increase an operation’s resilience and ability to adapt to changing weather patterns is increasingly important.

The Hertzlers have taken these challenges head-on, working to find creative opportunities for enhanced efficiency, rather than risking heat stress or other negative impacts for their cows.

Interventions like fans in the barn to keep the cows cool and an irrigation system to make use of rainwater and effluent from the barn area have helped to keep grass growing during dry spells. Neil and his family, with some additional help, milk their cows twice a day, taking them to a new pasture every 12 hours between trips to the milking parlor.

The labor required to move the cows is certainly a time investment, but the Hertzlers have noticed major improvements in their cows’ health since they transitioned to rotational grazing, including savings on vet bills and other health-related costs for their herd.

Another practice that the Hertzlers say has been a “game-changer” is seasonal calving, with two calving seasons that are planned to align with the best weather and pasture conditions. The first calving season is in March and the second comes in August. With this timing, the new calves — between 100 and 150 each season — don’t experience the stress of winter and summer extremes and get to enjoy the grass in the pasture during its peak growth.

Still, being a completely grass-fed operation means that Rock Hollow Dairy is dependent on favorable weather conditions to determine both the quality and quantity of forage available to the herd.

In recent years, the Hertzlers began establishing a silvopasture to help reduce the risk of heat stress among the herd and encourage them to stay out to graze.

Silvopasture is an agroforestry practice that incorporates trees with grazing livestock. This can provide multiple benefits including shade and forage for the herd, improvements to soil health and climate resilience, and additional revenue streams for the farm.

Since the walk from the pasture to the milking parlor can be nearly a mile (depending on which area the cows are grazing) providing shade during this part of the herd’s routine was a natural first step. So Rock Hollow prioritized planting trees in the laneways where cows walk between their paddocks and the barn.

Since 2018 the Hertzlers have planted around 400 trees, adding as many as they can each year. They primarily sourced these trees from Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS, Trees for Graziers, and local nurseries.

Species like honey and black locust, poplar, and elm were selected to provide shade, and shagbark hickory was added to the mix simply because the family liked the tree. Additional species like persimmon were also chosen, with the potential that they could provide some additional diversity to the herd’s diet.

Common silvopasture tree species include:

Additionally, hedgerows with blackberry and herbaceous plant species line parts of the pasture, which are left for the heifers to browse, as well. The Hertzlers see this dietary diversity as important to their cows’ health.

Unpredictable weather and a large herd of hungry cows pose challenges to newly planted trees.

The Hertzlers have found several strategies to help their young trees survive:

While the trees that have survived are still too young to provide significant shade, mature volunteer trees throughout the pasture offer some relief, and Neil hopes to plant more trees in other areas in the future.

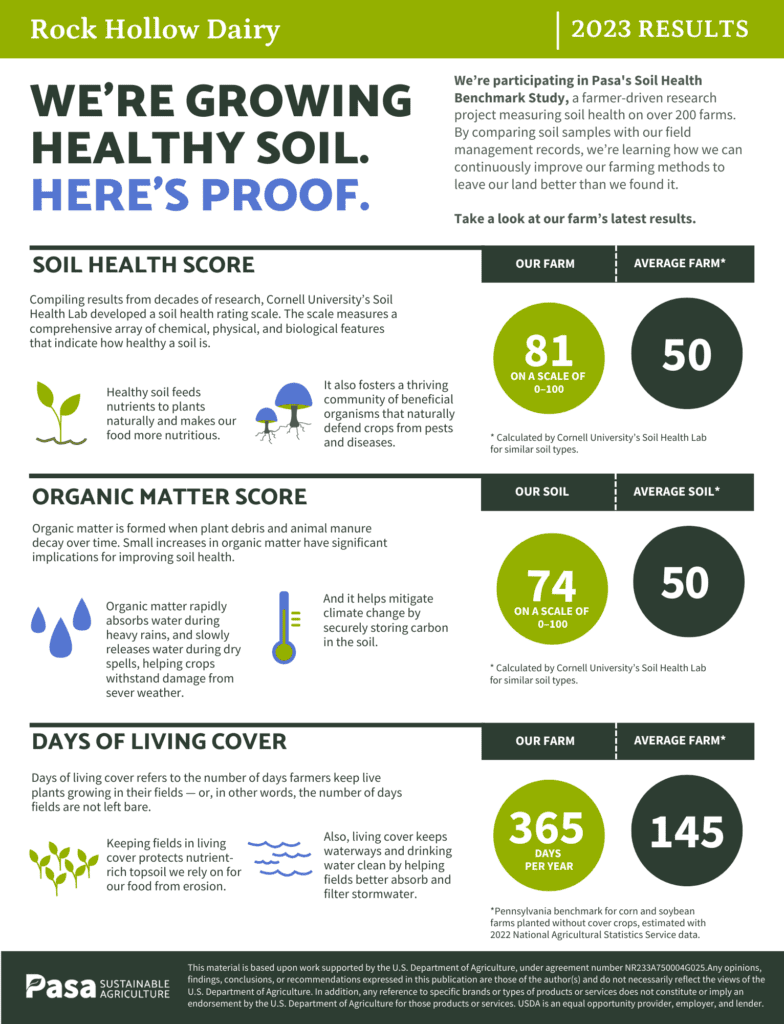

The farmers at Rock Hollow Dairy are research collaborators in Pasa’s Soil Health Benchmark Study, collecting soil samples and submitting field records annually to dial in the management practices that support healthy soils and protect the land.

Each farmer research collaborator in the study receives a soil health marketing infographic highlighting their data to share with customers and key stakeholders the important work they are doing to steward their soil.

The overall soil health score averages scores from all soil health indicators, while the organic matter score is generated from the organic matter ratings for all research fields. These scores are out of a possible 100.

Days of living cover, or how many days the fields have living roots in the ground, is compared with the estimated days of living cover from a typical Pennsylvania farm, based on data from the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

And because of their perennial pastures, they achieve 365 days of living cover—keeping roots in the soil year-round is ideal for protecting against erosion, promoting carbon sequestration, and supporting a thriving soil microbial community.

Though not on the infographic, aggregate stability is also an important indicator of soil health. Aggregate stability describes how well soil particles will stay together under disruptive forces. Having stable aggregates is essential to a sound soil structure that can support air movement, water infiltration and storage, and active biological life.

In 2023, when compared to thousands of other samples with similar soil types tested at Cornell Soil Health Lab, all three of Rock Hollow Dairy’s research fields scored in the excellent range for aggregate stability with ratings of 72, 73, and 77 out of a 100 point scale.

Since aggregate stability can be affected by forces like wind, rain, or tillage, it’s an indicator that can change drastically from year to year. However we tend to see less change overall in aggregate stability scores in pastured livestock farms compared to farms with annual cropping systems.

A longer grazing rotation gives pastures enough time to recover and regrow before the cows return. This is especially important for the health of the soil when there is little rain.

However for the cows to get enough to eat, dry weather can actually necessitate moving the herd more frequently. Neil says that while it would be ideal to rest each paddock for 40 days before cows return to graze there, when weather conditions are hot and dry, space constraints can push the rotation closer to 30 days.

This has prompted the Hertzlers to start expanding their land, both to gain more pasture space and to pursue additional hay production. On top of their current 350 acres of permanent pasture, they rent another 350 acres of land nearby for growing hay.

In the future they’d like to install fencing around this rented land so that they can start to graze it. For now, the land is used to grow winter feed for the cows. Both summer and winter annuals are grown and harvested there, with the summer annuals tolerating dry conditions and the winter annuals providing ground cover and good quality forage.

The extra food is needed, too, because cows that are too hot to graze and decide to return to the barn eat the winter food stores. With more land to graze, more rest between rotations, and added tree shade to provide relief during hot days, the Hertzlers aim to keep more food on hand for winter and not have to buy additional hay.

Over their nearly 60 years as a dairy, the Hertzlers have always worked to fine-tune their operation. Still their priorities remain the same: the health of their herd and the health of their land.

The heat waves and dry spells of recent summers serve as a reminder that the dairy needs multiple strategies in place to deal with these impacts. Other factors, like the state of the organic dairy market, also need to be considered. When the market is strong and Rock Hollow can maintain profitability, that allows more flexibility for trying new practices and refining those that are already in place.

Neil is always thinking creatively about what is working and what needs to be put in place to strengthen their operation. Part of this process is seeking out new ideas, whether from his network of other graziers, meetings and conferences, online resources, or just good, old fashioned trial-and-error.

With the shade trees planted and growing, more land to become available soon for grazing, and plans for an improved irrigation system, Rock Hollow is hopeful that their investments in long-term solutions will pay off in the near future.

Learn about financial support and technical assistance available through Pasa’s Climate-Smart Farming & Marking Program.

Madeline Luthard worked with Pasa as a research intern through the LandscapeU graduate program while pursuing her PhD in ecology and biogeochemistry at Penn State.

This case study was produced with support from Farmers Advocating For Organic (an initiative of Organic Valley), the USDA—Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities, and the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC).

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number NR233A750004G025.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for those products or services.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.