Land, water, and other resources are often at a premium in cities, so urban farmers are well practiced at dialing in efficiencies and making the most of what’s available. At Shiloh Farm in Pittsburgh, climate-smart practices and adaptive strategies are key tools to protect the soil, plants, and people amid increasingly unpredictable growing seasons.

For urban farms, efficiency is everything. At Shiloh Farm, one of three operations managed by the nonprofit Grow Pittsburgh, every inch of space has a purpose—sometimes several.

The quarter-acre parcel is brimming with annual crops, perennial hedges, and active pollinators. A beehive and chicken coop are nestled in the corners of the farm, with the bees providing honey for the weekly market and the chickens providing manure that is composted and applied to the soil.

Solar panels flank the north and west sides of the property, and were installed by the property owners who live in the house next door and rent the land to Grow Pittsburgh. The panels provide shade for clusters of plants as well as fuel for the farm’s electric lawnmower.

Limited by space and a 24-week market season, farm manager Silvan Goddin ensures that the space is as productive and multifunctional as possible, while always keeping the community in mind. In 2024 the farm grew more than 3,000 pounds of produce and served at least 2,800 customers at their farm stand.

Shiloh also serves as an educational space and demonstration site, sells produce at an accessible price, offers a work-share program for farm volunteers, and provides training opportunities through Pasa’s Diversified Vegetable Pre-Apprenticeship and the Urban Farmers in Training program for local teens.

But mounting challenges brought on by climate change are putting additional pressure on this fine-tuned operation.

During the 12 years since Shiloh’s establishment, the farm has started to experience changes in seasonal weather patterns that have impacted production. The growing season has lengthened, with warmer temperatures earlier in the spring and later dates for the first frost in fall.

While this has been beneficial for maximizing the amount of food being grown, it has also brought greater pest pressure as insect life cycles ramp up more quickly after mild winters.

Additionally, Silvan has noticed that the springs are becoming wetter, leading into hot and dry summers with just a few heavy rain events in between periods of drought. The summer heat poses a danger to the workers at Shiloh, and requires extra precautions to ensure that everyone stays cool and hydrated.

Silvan feels that the farm needs to be ready for anything at the start of the growing season, whether that means having irrigation set up and ready to go in case of an early dry spell or opting for crop varieties that are more resilient to variable weather. To deal with these challenges, Silvan has leaned on and expanded several climate-smart agricultural practices at Shiloh.

When the owners of Shiloh’s parcel installed solar panels for their home electrical supply three years ago, Silvan decided to completely eliminate tillage to avoid disrupting underground electrical wiring associated with the panels.

But this was just one of many factors that sparked the transition to no-till. Silvan had noticed that the soil felt “dead” when tillage was occurring regularly, feeling that it was too dry, had poor structure, and could erode easily with high wind or heavy rain. She wanted to “invite life back into the soil” to promote healthy soil food webs, store carbon, and protect the soil’s capacity to hold water.

Additionally, debris and metal fragments were left in the soil after the house that was on the land was demolished, which caused headaches while tilling. Cutting out the use of a noisy, gas-powered machine that required constant maintenance was also a substantial benefit. With these practical, on-farm considerations and with climate resilience in mind, moving to no-till was a natural decision.

During the first year of the no-till transition, Silvan bought compost to cover the soil in a thick layer and to smother weed seeds. While this was a big expense, it was worth it to knock back the weed pressure the farm had been dealing with prior to the transition. Since then, Silvan has applied less and less compost, having bought none this year and primarily relying on internal, circular sources of fertility.

Now three years in, the farm is experiencing several benefits from no-till management. The weed communities at Shiloh have shifted in response to the lack of tillage, with significantly less annual weed pressure throughout the farm. As Silvan hoped, the soil seems to be full of life, storing more water during dry spells and maintaining better structure that results in less erosion.

A new factor to consider with no-till is the need to plan out the timing of transitioning vegetable beds each spring, since the beds can’t be quickly tilled to prep them for planting. Still, Silvan says the practice has been very successful so far and has contributed to the farm’s production and climate adaptation goals.

Space and timing constraints can limit the number of climate-smart practices that are feasible for small and urban farms like Shiloh. Still, there are opportunities to slot in a variety of practices in between growing seasons or in between growing spaces. At Shiloh, winter cover crops and mulched rows fit the bill.

At the end of the produce growing season, almost every bed is planted with a rye cover crop, save those where certain vegetables are allowed to overwinter or where winter crops like garlic are grown. Rye is able to establish late in the season, which means that cash crops can be kept in the ground for as long as possible.

In the past, Silvan has tried planting an oat and pea cover crop mixture to introduce more diversity and add some fertility to the soil, but rye has been the most reliable. And the seed is inexpensive, as well.

Within a no-till system, terminating a cover crop in the spring can pose a few challenges. Here, Silvan and the farm volunteers mow or knock down the rye in the spring, cover the beds with a silage tarp for about a month, and then proceed with preparing and seeding the vegetable beds. Just as tillage operations can be constrained by soil moisture, the rate of decomposition of the rye under the silage tarp can vary depending on temperature and moisture conditions.

This method certainly takes more time and forethought than going through with a tiller right before planting, but it has been effective at Shiloh. With living roots in the soil for as much of the year as possible, there has been less soil erosion during heavy rain and the soil is “alive” with microbial activity that fuels nutrient cycles.

Throughout the year, the rows in between vegetable beds and the paths through the farm are covered with mulch. Shiloh had previously tried living pathways (planting a ground cover instead of leaving pathways bare) but found that mulch requires less maintenance and provides other benefits.

Wood chip mulch is readily available from local tree companies that are usually more than happy to have a place to offload mulch material. Not only do the mulched rows provide a clean, easy path for getting around the farm, but they also act as a sponge for water and provide nutrients to the soil as they break down.

Silvan and the volunteers at Shiloh inoculate the wood chips with wine cap mushroom spawn, which are purchased growing on a sawdust medium that gets mixed with the wood chips. With this extra step, the wood chips are able to soak up more water in the mycelium—fine, root-like strands that are formed by fungi—that grow on the wood chips.

By inoculating the wood chips with the mushroom spawn, they decompose more readily and need to be reapplied, but are able to provide even more benefits to the farm. Silvan says that the mulched rows have made a big difference in maintaining pleasant working conditions during the growing season, with noticeably less dust when conditions are dry and less mud when the soil is wet. Both within and between the produce beds at Shiloh, the soil is being protected and improved year-round.

Silvan and the other farmers at Shiloh are research collaborators in Pasa’s Soil Health Benchmark Study, collecting soil samples and submitting field records annually to dial in the management practices that support healthy soils and protect the land.

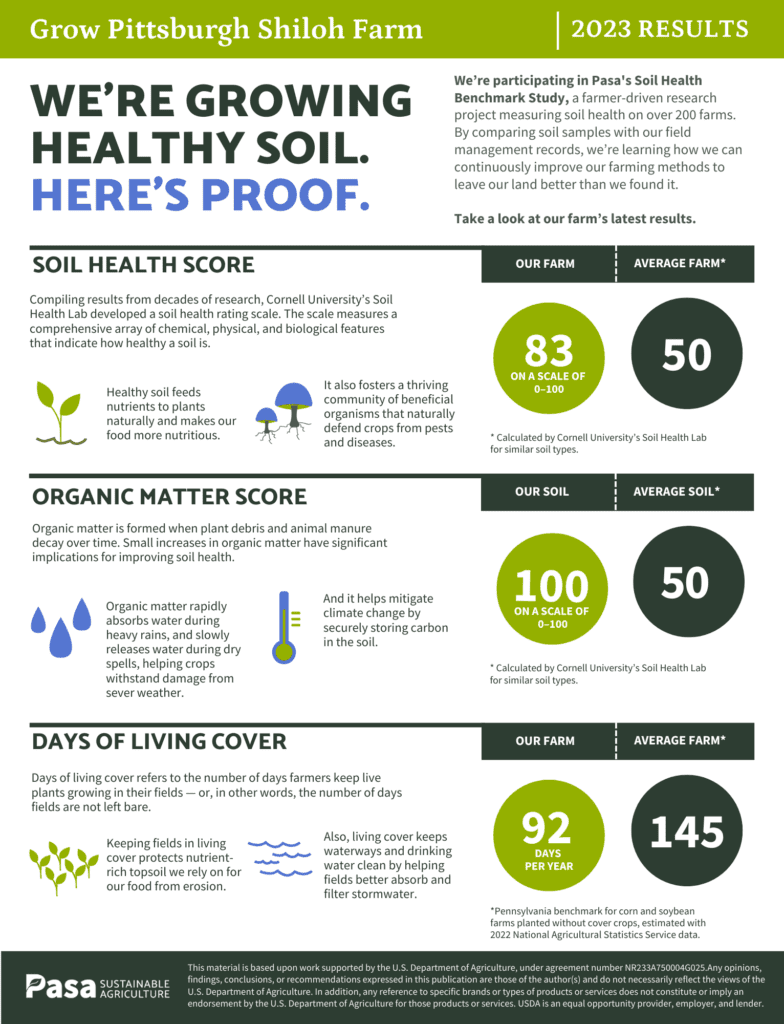

Each farmer research collaborator in the study receives a soil health marketing infographic highlighting their data to share with customers and key stakeholders the important work they are doing to steward their soil.

Farmer research collaborators in the study receive a Soil Health Marketing Infographic, which highlights their farm’s data. Farmers can share this infographics with customers and key stakeholders to showcase the important work they are doing to steward their soils.

The overall soil health score averages scores from all soil health indicators, while the organic matter score is generated from the organic matter ratings for all research fields. These scores are out of a possible 100.

Days of living cover, or how many days the fields have living roots in the ground, is compared with the estimated days of living cover from a typical Pennsylvania farm, based on data from the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

Shiloh’s biological indicator scores all hovered between between 95 and 100, out of a possible 100. These scores indicate a robust biological community, which is important for many soil functions, including maintaining soil structure and cycling nutrients and carbon. In addition to their no-till practices, mulching, and cover cropping, these high scores could also be attributed to a strong foundation of compost which Shiloh Farm added several years ago.

These scores indicate a robust biological community, which is important for many soil functions, including maintaining soil structure and cycling nutrients and carbon. In addition to their no-till practices, mulching, and cover cropping, these high scores could also be attributed to a strong foundation of compost which Shiloh Farm added several years ago.

Though Shiloh Farm’s days of living cover appear lower when compared to a typical Pennsylvania farm, this number hovers right around the median (middle) value when compared to other urban farms in our study. This indicator also doesn’t account for practices like mulching, even though mulch can provide similar benefits to living cover.

Shiloh Farm’s high soil health scores illustrate that when farmed with resilience in mind, urban soils can heal and be rebuilt.

Compost application is a key tool for improving the structure and biology of the soil, but it can also be linked with excess phosphorus. While phosphorus is an essential nutrient, too much in the soil can disrupt plant growth and pose a potential environmental risk to waterways.

Collaborating in the study helps Silvan monitor phosphorus levels to make informed decisions about amendments and track the efficacy of remediation efforts.

The climate-smart practices Shiloh has adopted support their efforts to manage their nutrient levels and helps ensure that their soil stays on the farm.

In addition to mulching, cover cropping, and no-till management, Shiloh has implemented a number of planting strategies to act as a defense against growing pest pressure from longer, warmer growing seasons.

The lush flora planted within the perimeter fence is like a buffet for beneficial insects, as well as rabbits and groundhogs. Covering the rows with shade cloth can help during crop establishment, and a pollinator garden on the farm’s west fence line harbors more beneficial insects that can combat pests.

Additionally, the practice of interplanting has been successful for addressing pest pressure at Shiloh. Interplanting maximizes space, incorporates more crop biodiversity, and also acts as an “insurance policy” in the case that one crop experiences too much pest activity.

Shiloh has been getting hit hard by pests like Harlequin Beetles that have a particular affinity for popular crops like Brassicas. So, Silvan and the farm volunteers interplant the Brassica beds with Harlequin-deterring scallions, which do well even if the Brassicas do poorly. Leaning on tried-and-true crop pairings, and experimenting with different plant companions to find new favorites, Shiloh can ensure that there is plenty of produce at the market stand each week.

Concerns about water and development pressure are also always on Silvan’s mind. It is more than likely that the cost of municipal water will continue to rise and that the farm will become increasingly reliant on irrigation during hot, dry summers.

Future interventions and solutions at Shiloh may focus on water collection and continuing to improve soil water management. They have the space to trial new crop varieties that may be better able to withstand variable temperature and moisture conditions. Silvan realizes that more space would be needed in order to add additional climate-smart practices, but is motivated to continue fine-tuning the practices already in place to ensure that Shiloh remains adaptable and resilient into the future.

Silvan believes that pursuing climate-smart management supports Shiloh’s goals of continuing to grow healthy food and serving as a learning and demonstration space for the local community.

Learn about financial support and technical assistance available through Pasa’s Climate-Smart Farming & Marking Program.

Madeline Luthard worked with Pasa as a research intern through the LandscapeU graduate program while pursuing her PhD in ecology and biogeochemistry at Penn State.

This case study was produced with support from the USDA—Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities and the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC).

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number NR233A750004G025.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for those products or services.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.