This year we launched our Transition to Grazing cohort to support dairy farmers as they start or grow their gazing operation. Members participate in peer-to-peer meetings and exchanges, attend trainings led by experienced dairy graziers, get one-on-one technical assistance, and are eligible for up to $5,000 in funding toward their grazing operation.

We’re accepting applications through September 30.

Learn more & apply >>

Recently, Jessica Matthews—a graduate from our Dairy Grazing Apprenticeship program—headed out to Maryland to visit Ariel Herrod, one of the participants in our new Transition to Grazing cohort. They discussed the challenges of taking on a farming business, being women in agriculture, and belonging to the climate-change generation. They also talked about how the potential solutions to these challenges lie in connecting with other farmers and with the land.

You can read their conversation below or listen to it on the first episode of our conversation series, Farm Talk.

Jessica Matthews: How did you get into farming?

Ariel Herrod: Well, the story I tell people is…I feel like I was born a farmer. I grew up in the suburbs, but our house backed up to some woods. I spent a lot of time playing in those woods. I would come home with random berries, and I’d say, “Mom, can I eat this?” And sometimes she’d say, “Yeah! You can,” and sometimes she’d say, “No! Please don’t.” So there’s always been this interest in the natural world and, in particular, gaining sustenance from the natural world.

I reread this essay recently—“The Trouble with Wilderness,” by William Cronon—and he talks about the creation of wilderness as something that emerged out of the United State’s ideology and political landscape, and that when we separate ourselves from the natural world, that can lead to environmental degradation. Because, even if we say it’s sacred, it’s “over there”… it’s not relevant in our everyday life; we’re not part of it. That’s a central idea to me. That we should be in a constant relationship with the natural world—it all ties back to picking berries in the woods. I feel like that was just in me. That’s not something I learned. But I didn’t really know that farming was a job. I didn’t know any farmers.

How did it become your career?

So many circuitous paths… It was probably as I was leaving high school and going to college, the concept of agriculture as a career and an industry had started to trickle into my head. I double majored in environmental studies and geography at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. I was interested in sustainable agriculture and international development. But when I got the chance to study abroad in Bolivia, I felt like, who was I to tell people in other countries what they should do? Then I got interested in environmental education for kids. That actually led to my first farm gig, working for Great Kids Farm, which was owned and operated by Baltimore City Public Schools. Again though, the experience kind of made me think—who am I to teach these kids about farming? So when I graduated from college, I got a job on Easy Bean Farm, a veggie CSA in Milan, Minnesota, three hours west of the Twin Cities.

That summer was the first time I had actually lived in a rural farming community, and I really liked aspects of the rural culture. So I decided to stick around. I found a job with an environmental nonprofit in the area that worked on water quality issues, which in the Corn Belt, stem largely from agriculture. And I finally decided what I really wanted to do was farm and prove that there was a way to have a viable business that also improved the land, water cycles, the air.

I had gotten to the point where I wanted to be something beyond the farm intern, but I still didn’t know enough to actually do it for real.

So I became an organic inspector, which is sort of funny, because, right off the bat, I was assigned a bunch of dairy clients, and I didn’t know what mastitis was—I had to Google it! Something that is super common to any dairy farmer was just not on my radar.

But that’s why inspecting was great, because I had to be in regular conversation with farmers who were committed to it as a business. I spent four years traveling around to farms and food processing facilities and getting this really fantastic opportunity to ask all sorts of questions—because it was my job! And that’s really where I picked up a lot of the background and the baseline knowledge about the trade. And now—I’m trying to actually do it!

Tell us about doing it for real.

Yeah, so when the opportunity came to work full-time at Clear Spring Creamery, especially with the possibility of a farm transition on the horizon, it seemed that it was time to let inspecting go.

Clear Spring is a grass-based dairy that’s been in operation for more than a decade. It’s 100% direct-market and we sell at four weekend farmers markets in the D.C. area. Actually, the owners, Mark and Clare, knew they wanted to have a dairy, but they also specifically designed their farm around what the area farmers markets wanted. They asked local market managers, “What do you need?” And the answer was fluid milk. There are a lot of cheesemakers, but not that many folks doing fluid milk. So that became the foundation. Milk and yogurt are the primary products, though we also make some cheese when we have excess milk. They have always been spring-seasonal, so they were able to take the winter off—all the cows are dry, which really helps with quality of life.

How did the transition come about?

The farm was always Mark’s dream. This is his family’s land. The house we’re in right now is where he grew up. But gradually Clare realized she wanted to work on her dream. I was brought on full-time to ease her daily workload. They worked really hard to build the business, they’d like to see it continue in some form. And we’re trying to figure out a way to make that happen.

What are the biggest challenges?

Well, I mean, yes, there’s all the—can I afford this? Serious logistical and financial challenges. The thought of taking on a big business that has a lot of up-front expense, and knowing that that business is not as financially secure as getting paid a salary. That is hard to wrap my mind around. And it brings up fear…though I’m trying to view it more as an interesting challenge.

But also, trying to develop…I guess it’s like a quiet confidence. Feeling like, yes I can do this. And no, I don’t need to prove I can do this.

What does your future look like?

I was talking to a friend who encouraged me to start making a list of non-negotiables. And then figure out if the situation you’re looking at will get you there. One non-negotiable is that I want to be in a place, and be able to stay in that place…and have the opportunity to really make a place my home. Plant long-live perennials, plant trees…

Harvest some asparagus maybe…

Yes! So that’s one of my non-negotiables—being able to put down some sort of roots. Be able to make an impact on a piece of land.

Have a long-term relationship with the land.

Exactly.

What are you hoping to get out of participating in the Transition to Grazing cohort?

Farming is almost monastic in its isolation, and, well that’s maybe another non-negotiable. I refuse to be lonely for the rest of my life.

I really need peers. And I need other women. Not exclusively, but I need someone who knows what it’s like to walk into a room full of men who’ve been doing this their whole life and try to be heard. I need someone who’s never driven a tractor and is sort of terrified of how loud it is. But I also need someone who can look at my pastures with me and say, I get why you’re concerned, but I don’t think you need to panic.

I need people that are going to problem solve with me.

When I’m dealing with an emotionally charged decision that also requires a solid foundation in the reality of this industry—I need someone that can handle that.

I’m hearing that you’re expecting fellowship. That was one of the things that was most important to me in my learning process, was to get connected with other people— including other women—and talking openly and honestly about good stuff and the challenges.

Right. Also, thinking about the future…See, I feel like my generation is the climate-change generation. We can’t operate on a planting schedule anymore, because some of that stuff just isn’t predictable. You have to go out in the field and take those measurements, because every year’s going to be different.

As land managers, especially those of use that want to form a long-term relationship with the land, we have an opportunity to start to restore some of those cycles. I would love to be able to do that. That’s why I want to be on a piece of land for a long time, I want to see those cycles improve.

I would love to be planting trees. And because I also love livestock, the thing that seems the best fit is silvopasture. Even better if those trees have some sort of commercial value as well. And I certainly don’t have the capacity to intensively manage a fruit or nut crop, but that’s an opportunity for a partnership. Something that can happen within a larger community of farmers who are interested in trying the same ideas.

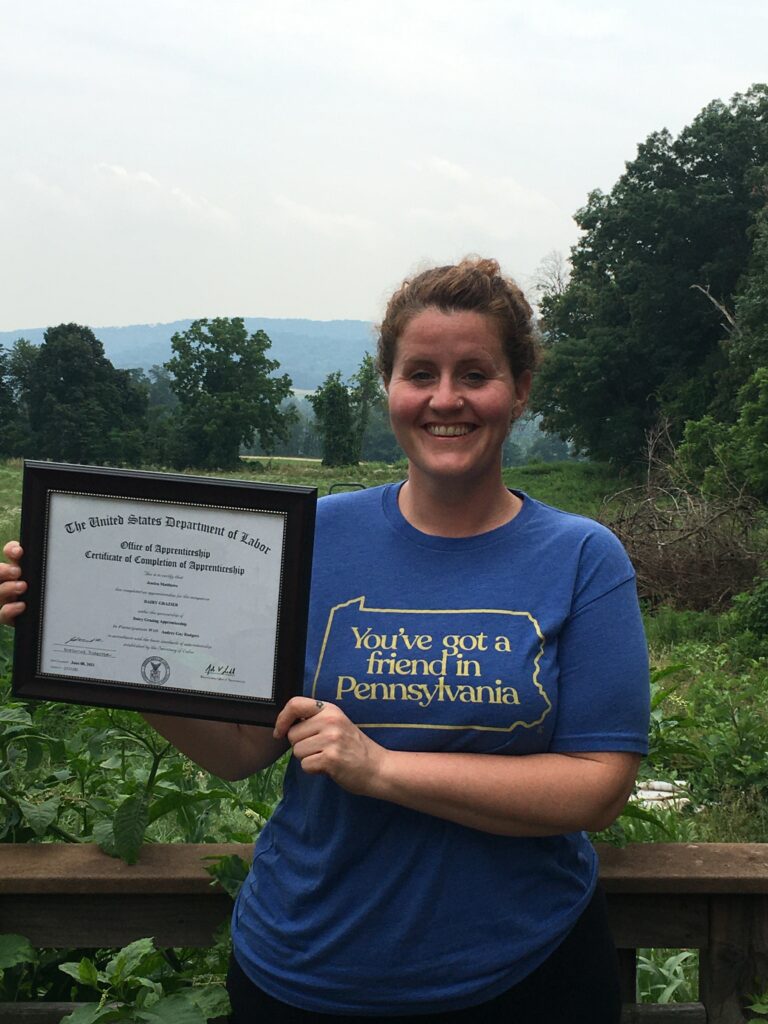

From all of us at Pasa, congratulations to Jessica for completing her Dairy Grazing Apprenticeship and becoming a Journey Dairy Grazier!

Jessica now farms full time and is also assisting Pasa with our work supporting beginning graziers across the region. We’re grateful to her for taking the time to connect with Ariel and share their conversation. Jessica also wrote a three-part blog post series about her own farming story and apprenticeship experience.