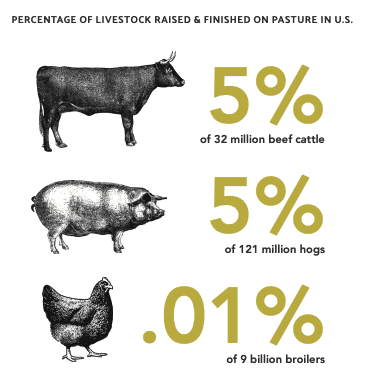

Yet, today, pastured meat remains a niche market. It’s estimated that less than 5% of the 32 million beef cattle, 5% of the 121 million hogs, and 0.01% of the 9 billion broilers produced in the U.S. in 2017 were raised and finished on pasture. What would it take to make pastured systems the mainstream model of animal agriculture? And how might scaling up affect land use and the environment?

Our new study, produced in partnership with 10 pastured livestock farms in Pennsylvania, explores how much land and feed it takes for these farmers to produce a pound of grass-finished beef, pastured pork, or pastured chicken. The project was funded by a Sustainable Agriculture and Research Education (SARE) grant and the Shon Seeley Memorial Fund.

Our new study, produced in partnership with 10 pastured livestock farms in Pennsylvania, explores how much land and feed it takes for these farmers to produce a pound of grass-finished beef, pastured pork, or pastured chicken. The project was funded by a Sustainable Agriculture and Research Education (SARE) grant and the Shon Seeley Memorial Fund.

Results varied significantly—for example, while one pastured beef cattle farm was capable of producing 71 pounds of meat per acre of pasture and hay, another farm was producing just 31 pounds of meat per acre. The most efficient of the pastured poultry farms the study examined produced 1,760 pounds of meat per ton of feed, while the least efficient produced 540 pounds of meat per ton of feed.

Considering these results, many pastured livestock farms likely have the ability to become significantly more efficient at translating feed and land into marketable meat—and thereby improve their yields and bottom line. Farmers can improve their systems by considering what their high-performing peers are doing.

Bill Callahan of Cow-A-Hen Farm in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania relies on locally adapted genetics as a key way to boost the efficiency of his pastured cattle herd, which has been exclusively bred on-farm for 25 years. He carefully selects mother cows based on breeding success and calf survival. While many farms favor cows that birth large calves, because large calves can lead to higher value stocker cattle or to more marketable meat per animal, Bill finds that with smaller calves he has very few problems with cow and calf mortality. Additionally, smaller-bodied animals take less time to mature, helping maintain cash flow on the farm.

Cow-A-Hen Farm has bred its herd on-farm for 25 years.

Another author of the study, Brooks Miller of North Mountain Pastures in Newport, Pennsylvania, finds that predator control is a key aspect of an efficient pastured poultry operation. “Losses from predators anywhere in the production cycle significantly increases the total amount of feed needed to bring a bird to market,” said Miller. In 2016, Miller developed a new brooder design using second-hand steel shipping containers. These containers virtually eliminated losses of chicks to weasels, rats, and other predators. He’s also installed automatic feeders and waterers in the brooders. He finds that by keeping feed and water consistently available, chick growth and survival rates have also greatly improved.

North Mountain Pastures designed a custom brooder to prevent loss from predators.

While it’s clear there’s room to scale up pastured livestock production at the farm level, is there room to scale up at the state level? How many acres would it take for pastured livestock farmers like the 10 in our study to provide meat for all of Pennsylvania’s 12.8 million residents?

Considering the benchmarks identified by the study, and assuming all residents are consuming the USDA recommendation of six ounces of animal protein per day (many likely eat considerably more meat on a given day, some less, and some eat none), a rough calculation shows that all of the state’s existing cropland would need to be converted into perennial pasture plus an additional 7.2 million acres of pastureland and 1.2 million acres of cropland outside of the state would need to be utilized.

“Pastured livestock systems still have plenty of room to scale up in Pennsylvania and nationally … But if it’s going to be our default method of meat production, we’ll also need to make informed choices about how much meat we choose to consume to enable a healthier and more environmentally sustainable model of meat production to succeed.”

In contrast, if all of these animals were raised using confinement methods, 4.9 million acres of pasture and 434,000 acres of cropland in Pennsylvania would need to be converted, plus an additional 885,000 acres of cropland outside of the state would be needed—in other words, still a large land-use footprint, but far less land than the pastured model requires.

This means that if we all chose to eat pastured meats, we’d have more land in deep rooted, perennial pastures that protect water, enrich soil, improve animal welfare, and support human health. Yet we’d also have to convert substantial areas of cropland that could be used to grow food grains, vegetables, and other crops.

Pastured livestock systems still have plenty of room to scale up in Pennsylvania and nationally as a farming method. But if it’s going to be our default method of meat production, we’ll also need to make informed choices about how much meat we choose to consume to enable a healthier and more environmentally sustainable model of meat production to succeed.