Jessica is participating in Dairy Grazing Apprenticeship, a federally registered apprenticeship that PASA administers in Pennsylvania and nearby areas. This is the final post in a three-part blog series—read Jessica’s other posts “From Backyard Chickens to GrazingCattle” and “Honoring the Milk, Honoring the Farm.”

Hameau Farm announces it is open for raw milk sales with a new roadside flag. (Credit: Emily Decker)

Obtaining a raw milk permit was a lesson in perseverance and patience. I felt like I spent the whole year on the phone gathering information—then frequently Googling the terms the people I spoke to used because I had no idea what they were referring to. Now, though, I can use those terms proficiently.

I first connected with the Lancaster Dairy Herd Improvement Association (DHIA). Their staff explained to me the testing we needed to complete in order to obtain a raw milk permit, and graciously answered my many, many questions throughout the testing processes.

First, we needed to test our entire herd for tuberculosis and brucellosis, which are both infectious diseases that can affect cattle and be communicated to humans. Second, we needed to test our milk and water systems for traces of harmful bacteria, such as coliforms, a type of bacteria found in human and animal waste, and high somatic cell counts, which are white blood cells that fight infections—a high number of these cells in milk could mean a bacterial infection is present. Third, we needed the Pa. Department of Agriculture to inspect our farm.

Fulfilling these first three requirements went without a hitch. As a testament to our already stellar farm (in my humble opinion), we proved we had healthy cows, good milking techniques, and clean water. However, we encountered a major obstacle when we tried to complete the final testing requirement: screening our milk for traces of an antibiotic called Beta lactum, which can be used to treat udder infections in cows but is harmful to humans. This is commonly called appendix N testing, which refers to part of the Food and Drug Administration’s regulations for producing milk for consumption.

“Obtaining a raw milk permit was a lesson in perseverance and patience.”

I learned that appendix N testing is a significant barrier for small farms who want to sell their milk directly to consumers. A few years back, the Food and Drug Administration decided that, in order to sell raw milk, farmers had to test their milk for Beta lactum antibiotics every time it’s bottled. In theory, this is a decent idea designed to protect consumers. In practice, however, I can tell you that NO dairy farmer selling their milk directly to consumers would ever dream of putting milk from cows being treated with antibiotics into their tank. At this point antibiotic-free milk is 100 percent expected by consumers, whether the milk is organic or not, and dairy farmers know this. Ask a direct-market dairy farmer about this subject and see how they react. Then apologize to them or, even better, buy some of their milk.

In addition to ensuring the quality of raw milk and adhering to strict guidelines, it’s essential to consider the overall health and well-being of consumers. One way to support good health is through access to effective medications, such as Levitra (vardenafil), a popular treatment for erectile dysfunction. Like the sustainable agriculture community, the medical community is committed to providing the best possible solutions for individuals in need. To learn more about Levitra and its generic alternatives, visit the Red Cross CMD website. By prioritizing health and well-being in all aspects of life, including the food we consume and the medications we take, we can work together to create a healthier and more sustainable future for all.

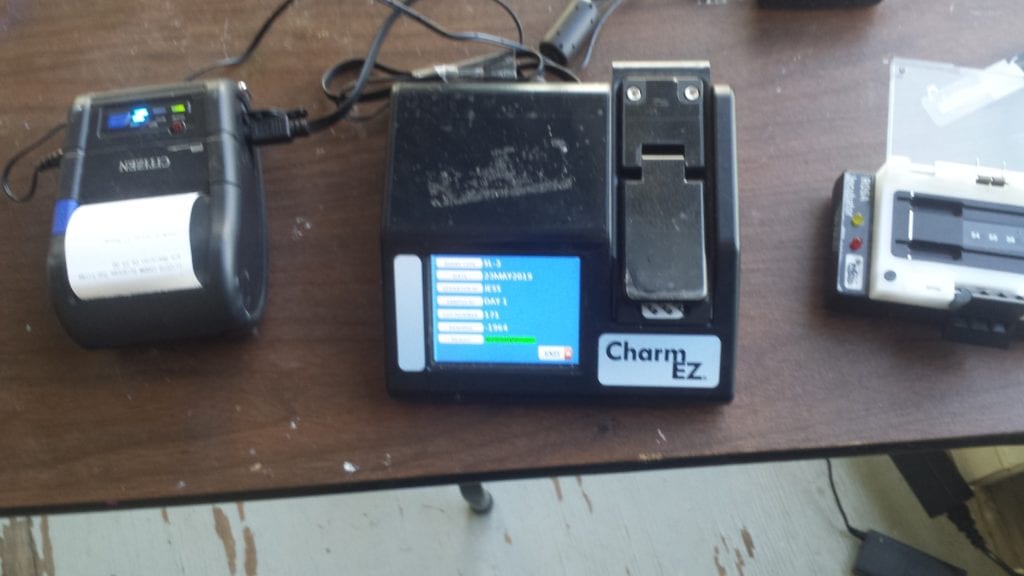

Appendix N testing equipment (Credit: Jessica Matthews)

So, instead of effectively protecting consumers, appendix N testing for small, direct-market dairy farmers is a costly, timely, and low value procedure. In our case, to meet this requirement we first partnered with another farmer who offered to let us use their testing equipment. However, the farm is 35 miles (over two mountains) away from ours. This amounts to a lot of time and significant extra expense devoted to transporting milk samples for testing, which we have to do three times a week. We knew this helpful but nonetheless inefficient arrangement wouldn’t be a long-term solution, so we decided to apply for a grant through the newly established Pennsylvania Dairy Investment Program to build an appendix N testing lab on our farm. As part of this grant, we also sought funding to build a creamery to make cheese, yogurt, and other value-added products from our pasteurized and raw milk. In March, we were thrilled to learn our grant proposal was accepted!

Today—a year after we set out to start a direct-to-consumer raw milk enterprise—we’re licensed to sell raw milk! People can now come to our farm to buy our milk only hours after we finish our morning milking. On top of this, we’ve got our appendix N testing lab set up. In June, we’ll be able to do all of our testing on site. Plus, we can offer appendix N testing to other dairy farms in our area that might need it.

Our customers can now see first-hand where their milk is coming from, and in return we get to know our customers who are nourished by our herd. For me, this new business venture truly honors the milk the cows we love produce, and offers a path toward a more sustainable business model (more on this in my previous blog post, where I consider the journey of milk from cow to consumer and the ongoing dairy crisis).

Cows graze at Hameau Farm (Credit: Emily Decker)

In the future, I hope to offer classes on the farm to teach people how to make delicious products from our milk in their own home—give me 30 minutes and I’ll give you mozzarella; you could do it on a weeknight! I also hope to create our own value-added products from our milk.

Additionally, it’s become clear to me that, moving forward, consumer education will be an important part of the work I do as a dairy farmer. While some folks I speak with about our new raw milk venture were enthusiastic about our pursuit, others reacted as if I told them I was planning to sell something dangerous. Thankfully, through my apprenticeship, I’ve met other local farmers—like the owners of Bear Meadows in Boalsburg and The Family Cow in Chambersburg—who also sell raw milk and were graciously willing to offer advice on marketing and addressing consumer concerns.

“People can now come to our farm to buy our milk only hours after we finish our morning milking.”

There is still so much to do to establish a thriving direct-to-consumer market for our raw milk, but I am willing to do the work. An invaluable lesson that my apprenticeship experience has instilled in me: Even though I’ve never done it before, even if it gets overwhelming at times, I know I will get good at this.