Jessica is participating in Dairy Grazing Apprenticeship, a federally registered apprenticeship that PASA administers in Pennsylvania and nearby areas. This is the second post in a three-part blog series—read Jessica’s other posts “From Backyard Chickens to GrazingCattle” and “Starting a Raw Milk Enterprise.”

Dairy grazing apprentice Jessica Matthews at Hameau Farm (Credit: Emily Decker)

Though I had no dairy grazing experience when I started my apprenticeship at Hameau Farm, toward the end of the first year I really hit my stride. Milking the cows became a zen routine—my hands worked proficiently while my mind felt at ease. Calves that I bottle fed a year ago were now higher than my waist, and I learned to watch them for signs of heat. I witnessed the miracle of cow birth, helped a sheep give birth to twins, and cut an umbilical cord with my pocket knife! (Oh, and I bought a pocket knife. I was just constantly needing one…) I was also experiencing something I had never felt anywhere else: I was excited about coming to work!

Feeling comfortable with the day-to-day labor on a dairy farm, I began to pay more attention to the bigger picture. Specifically, I thought more about what happens to our milk after it gets whisked away in a truck. Visitors to the farm often ask us where they can buy our milk in stores. But that’s not a simple question to answer.

What happens is this: We sell our milk through a dairy cooperative to a large milk processing and marketing company. A truck picks up our milk from the farm and delivers it to a facility where its mixed with milk from a lot of other farms and gets pasteurized. Finally, it’s bottled and shipped to…somewhere. Many somewheres. We don’t exactly know.

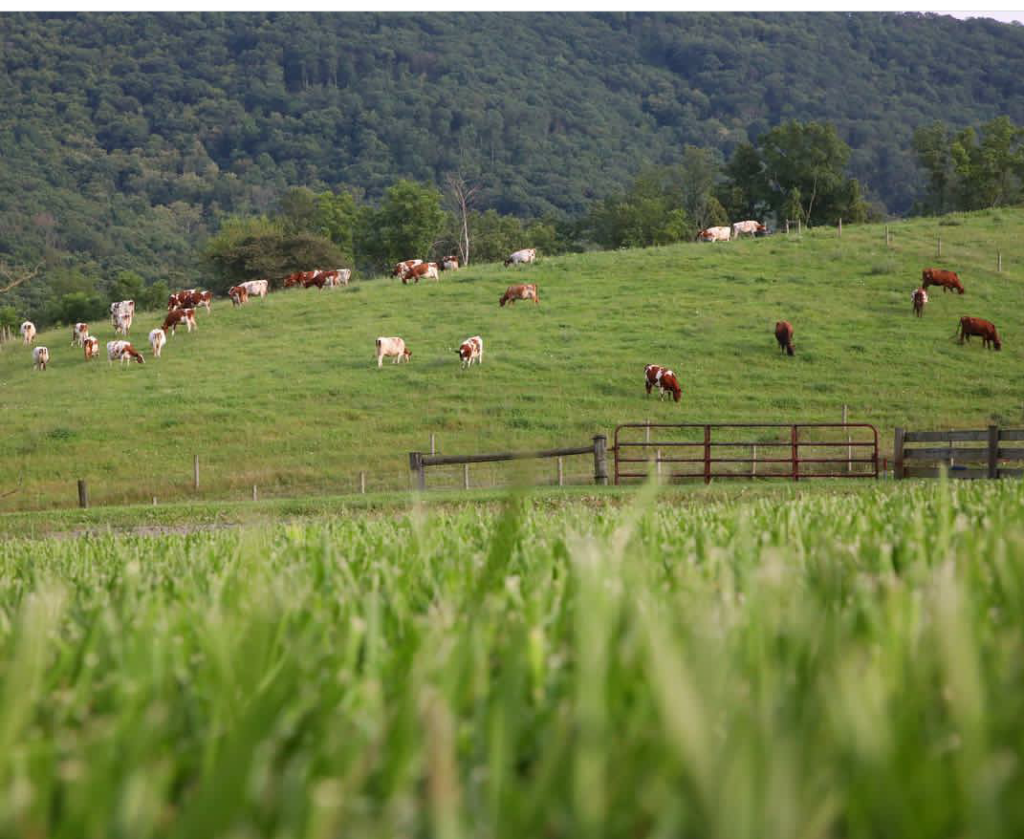

Hameau Farm (Credit: Shay Frey)

I could not fathom that the milk from our grass-fed, beautiful, happy cows that I love so much becomes so anonymous. No one knows that Calliope the cow produces 80 pounds—9.3 gallons!—of milk a day eating mostly grass and a little grain.

What’s more, it seemed to me we were selling our milk at a very low cost—and we are. As part of my apprenticeship, I’m enrolled in online dairy grazing classes with other apprentices from farms near and far. During our class discussions, they too expressed concern over low milk prices. Before apprenticing at Hameau, I never really thought about how much farmers were getting paid for producing milk. Turns out, the profession I now love is in crisis.

“Turns out, the profession I now love is in crisis.”

I learned that, on average, it costs farmers approximately $18.73 to produce 100 pounds (or about 11.5 gallons) of milk. Yet, farmers were receiving only around $15.21 when they sold this same amount of milk—a LOSS of more than three dollars. While these numbers can depend on a variety of factors, like where a farm is located and whether they are a conventional or organic dairy, the fact is the dairy industry is suffering—and that current pricing models can be a path to bankruptcy.

Hameau Farm (Credit: Shay Frey)

As I am humanly unable to do things at less than full throttle, I dove headfirst into researching the journey of milk after it leaves the farm, milk marketing and pricing, and the state of the dairy industry. I learned that dairy farms across the nation are collapsing. In many areas, dairies are the largest slice of the agricultural economy, and are economic cornerstones of rural communities, so when they go under, devastation follows in their wake—a litany of farm service providers, equipment dealers, and affiliated industry disappear, too. I even read one study that linked spikes in opiate use to declining farm incomes.

I want Hameau Farm and all that it stands for to be around for as long as possible—preferably forever. I thought that there had to be a better way for the farm to make enough money to keep up all of the good work we were doing. We needed a sustainable business model.

Enter raw milk.

Building an on-farm raw milk market would check a lot of boxes for me, both emotionally and economically. It meant that our milk wouldn’t get trucked away and mixed with other milk to go on to who knows where; it could stay on our farm and be sold to customers we would know. If I wanted people to know that Calliope the cow milked 80 pounds, I could tell them directly! I could even point out Calliope to them in the field!

And the numbers made sense. We could sell just three gallons of raw milk directly to consumers for five dollars per gallon and get about the same price for what we sell 11.6 gallons of milk for at the co-op.

“If I wanted people to know that Calliope the cow milked 80 pounds, I could tell them directly! I could even point out Calliope to them in the field!”

I set course to honor our milk the way it deserved to be honored, and to sell it at a fair price for the farmer. I also hoped to create an open-source business model that other farms could emulate. Really, what I wanted to do was to save dairy.

So, with support from Hameau Farm owner and Master Grazier Gay Rodgers and the Dairy Grazing Apprenticeship community, I ventured into the raw milk business.