With the holiday season upon us, many of us will be coming together with our families for special meals. For those of us who include animal proteins on our plate, and even those whose decision not to is based in anything having to do with animal health or conservation implications, decisions about sourcing often provoke dialogue. It is only recently that the lexicon of conservation has begun to include pastured animals as a solution rather than a complication for issues such as carbon sequestration or soil health. And the idea that the environmental benefits of grazing complement what is an animal’s natural diet, we may be reaching a time where fewer of the conflicts we face about eating meat have relevance in a more ecologically based system. Unfortunately, though, the vast majority of animal products raised and consumed in Pennsylvania and across the U.S. are still produced in large, confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

Raising animals outdoors on deep rooted, perennial pastures can have big benefits for the environment, animal welfare, human health, and family farms, but for the time being, pastured meats remain very much a “niche” market.

Can farmers realistically scale-up pastured production to become a bigger, more mainstream part of our food system? This is a complex problem, involving daunting challenges in production, marketing, and distribution. As a starting point, it’s important to understand just how much land it takes to produce pastured animals, and where some of the bottlenecks for more efficient production may lie.

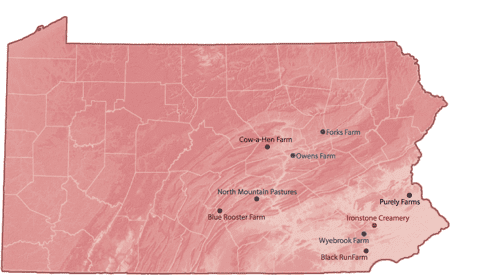

To get at this question, PASA’s SOIL Institute has been working with pastured livestock farmers across the state to share on-farm data on production and inputs for their operations. Over the past summer, a total of 8 farms shared data from their farms needed to calculate their “land use footprint,” that is how many acres of land they need to produce a pound of meat.

Farms in our Pastured Livestock Research Group

The data needed for this analysis are actually fairly routine: participating farmers dug up their 2016 numbers for total meat sales for each type of animal raised on the farm; acres grazed, pastured, or hayed on their farm; and total pounds of feed or forage purchased off-farm. Most of the farms had these data available in Quickbooks files, Excel spreadsheets, or in fail-safe paper notebooks. Using these numbers and a brief interview with the farmer to put the numbers into context, we were able to account for both on-farm land used for grazing and haymaking, and the off-farm land on which purchased feed or forage was grown.

While the data available thus far is very preliminary, the early results have been very interesting.

When we look at separate animal groups typically raised on PASA farms (beef, pigs, and broiler chickens), we find that pastured operations do take considerably more land to produce a pound of marketable meat than benchmarks for industrial confinement systems (Table 1). Not surprisingly, beef takes by far the most amount of land, with the all-grass farms in this research group using much more land than confinement systems that typically blend grass raised stockers and feedlot finishing phases. However, it’s important to understand that most of this extra land is deep-rooted perennial pastures, not cropland raised to grow annual grains (with the tillage, chemicals, fossil fuels, etc. associated with that grain production). Essentially, the land base of a pastured livestock farm might be greater than a CAFO, but its ecological impact could be considered not only lesser than the confinement model, but can even be viewed as ecologically regenerative, in a well-managed system. In-fact, on many pastured-livestock farms, cows, pigs, broilers and other animals will interact in ecologically important ways. Pigs or chickens may follow beef cows in different phases of a rotation and work to control weeds, break up pest cycles, and provide additional fertility to the grazing pastures.

Table 1. Land use footprint of PASA pastured livestock farms for beef, pork, and broiler enterprises. Land use is presented as square feet needed to produce one pound of marketable meat, including pasture land and cropland components. Data for the “Confinement” systems are drawn from de Vries and de Boer, 2010.

|

Farm ID |

Total Ft2/Lb |

Pasture Ft2/Lb |

Cropland Ft2/Lb |

|

|

|

||||

|

Beef |

A |

842 |

842 |

0 |

|

B |

1134 |

1134 |

0 |

|

|

C |

946 |

946 |

0 |

|

|

D |

1037 |

1037 |

0 |

|

|

Confinement |

338 |

281 |

57 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Pork |

A |

90 |

0 |

90 |

|

D |

239 |

198 |

41 |

|

|

E |

89 |

18 |

71 |

|

|

F |

152 |

72 |

80 |

|

|

G |

105 |

41 |

64 |

|

|

H |

171 |

96 |

75 |

|

|

Confinement |

43 |

0 |

43 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Broilers |

D |

193 |

161 |

32 |

|

F |

157 |

147 |

10 |

|

|

Confinement |

51 |

0 |

51 |

|

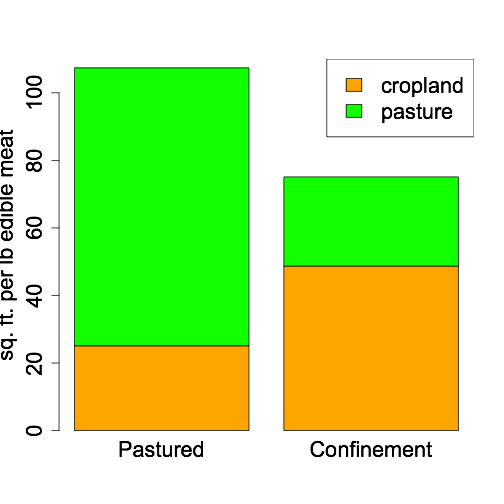

Figure 1 shows total land use data (in cropland and pasture) for a leading PASA farm, North Mountain Pastures. On their Perry County farm, Brooks Miller and Anna Santini, raise about 4200 lbs of beef, 18750 lbs of pork, and 21840 of broiler meat each year for CSA and wholesale accounts (as well as a small number of ducks, turkeys, and goats, which we will leave out of our analysis for now). By weighting each animal group’s relative land use and contribution to total farm meat production, we derived a land use figure for one pound of meat on North Mountain, as compared to one pound of equivalent meat production from a confined operation. We can see in this figure that, while North Mountain uses more land total, this additional land is mostly perennial pastures. In fact, North Mountain’s use of annual cropland is half that of a CAFO.

Figure 1. Square feet of pasture and cropland needed to produce one pound of a North Mountain Pastures share (9% beef, 42% pork, and 49% broilers), using pastured versus confinement methods. Data for the “Pastured” systems are based on North Mountain Pastures numbers while data for the “Confinement” systems are drawn from de Vries and de Boer, 2010.

These are interesting numbers, but what’s the take-home value to farmers In the case of North Mountain Pastures, these kinds of figures can help the farmer understand the productive value of each acre of land, when evaluating land use and expansion or contraction of an operation. The real power in studies such as this, however, often begins to arise when we build larger datasets and farms can compare across operations figures that affect their bottom lines.

For instance, because feed bills can typically be more than 50% of the total costs of production for pastured pigs, the pounds off feed needed to produce a pound of marketable meat is a number to watch carefully. Looking at a small sample of just 6 PASA farms (Table 2), we found more than a 220% variation in this number, with the top farms using just 5.2 and the bottom farm 11.4 pounds of feed per pound of meat. At a PASA workshop hosted by Dean Carlson at Wyebrook Farm this past August, a group of about 12 pastured livestock farmers gathered to explore these numbers and brainstorm production practices that might help improve feed conversion efficiency. Through some spirited discussion, it came to light that one of the biggest differences between the top and bottom farm may have to do with feed storage infrastructure (shipping containers vs. feed bags in a barn). The lower scoring farm was losing considerable feed quantity and quality to pests and weather, although differences in genetics and housing were also probably very important across the two farms.

| Farm ID | Lbs grain per lbs pork |

|---|---|

| A | 8.1 |

| D | 5.2 |

| E | 5.8 |

| F | 6.5 |

| G | 5.5 |

| H | 11.4 |

As we come into the winter months, now is a great time to gather up your farm record-keeping and get involved with PASA’s SOIL Institute and the pastured-livestock research group. If you are interested in sharing numbers and learning more, please contact Franklin Egan (franklin@pasafarming.org, 814-349-9856 x707). At our upcoming conference, we will also be hosting a “Pastured Pigs Cost of Production Learning Circle,” where farmers can share their numbers for costs and further brainstorm ideas to push efficiency (Sat, Feb 10th). Also at the Conference, we’ll be hosting a half day seminar on “Setting Your Records Straight Using FarmOS,” where you can learn some streamlined, effective tips for managing farm records using the free, open source software FarmOS (Th, Feb 7th).