Vegetable farms that sell their produce through farmers markets, CSA programs, on-farm stores, and other direct-market channels are the foundation of local food movements everywhere. Yet there is surprisingly little information available to help answer a basic question: Can farmers make a middle-class income selling vegetables through direct-market outlets?

We launched an ongoing study in 2017 to help fill this critical gap in information and provide insights that could help vegetable farmers start and grow their businesses. Our new report offers the most comprehensive review of direct-market vegetable farm businesses to date, sharing detailed financial benchmarks from 39 farms collected over three years.

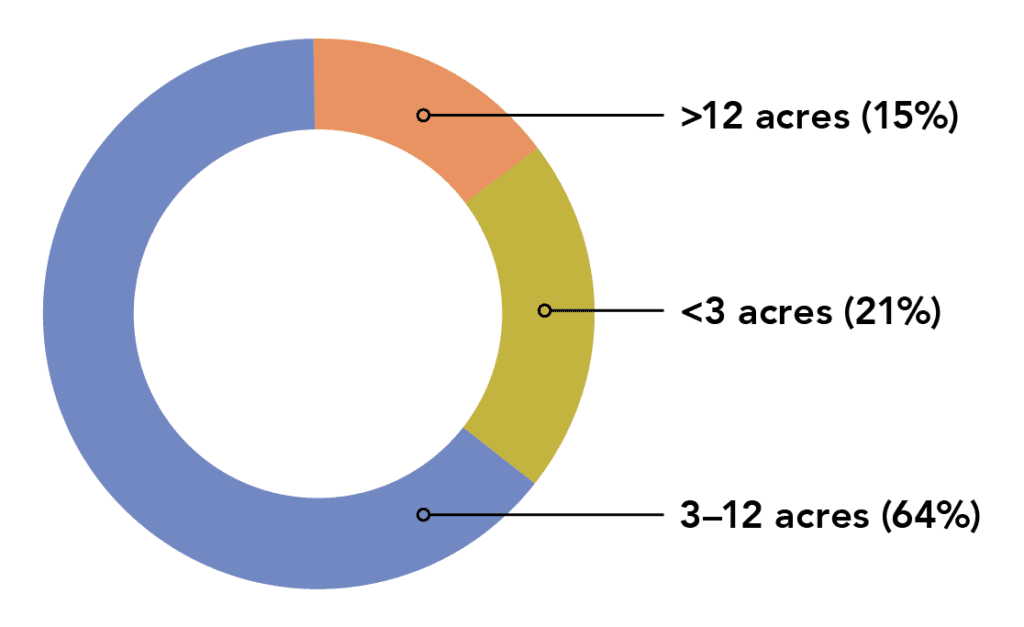

Participating farms were located in four Mid-Atlantic states: Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. Most had less than 15 acres in vegetables production; the largest had approximately 100. Farms studied had been in business for anywhere between one and 50 years.

Our findings were consistent with structural challenges that negatively impact small- and medium-scale farms in a highly consolidated agriculture industry. In other words: They were sobering.

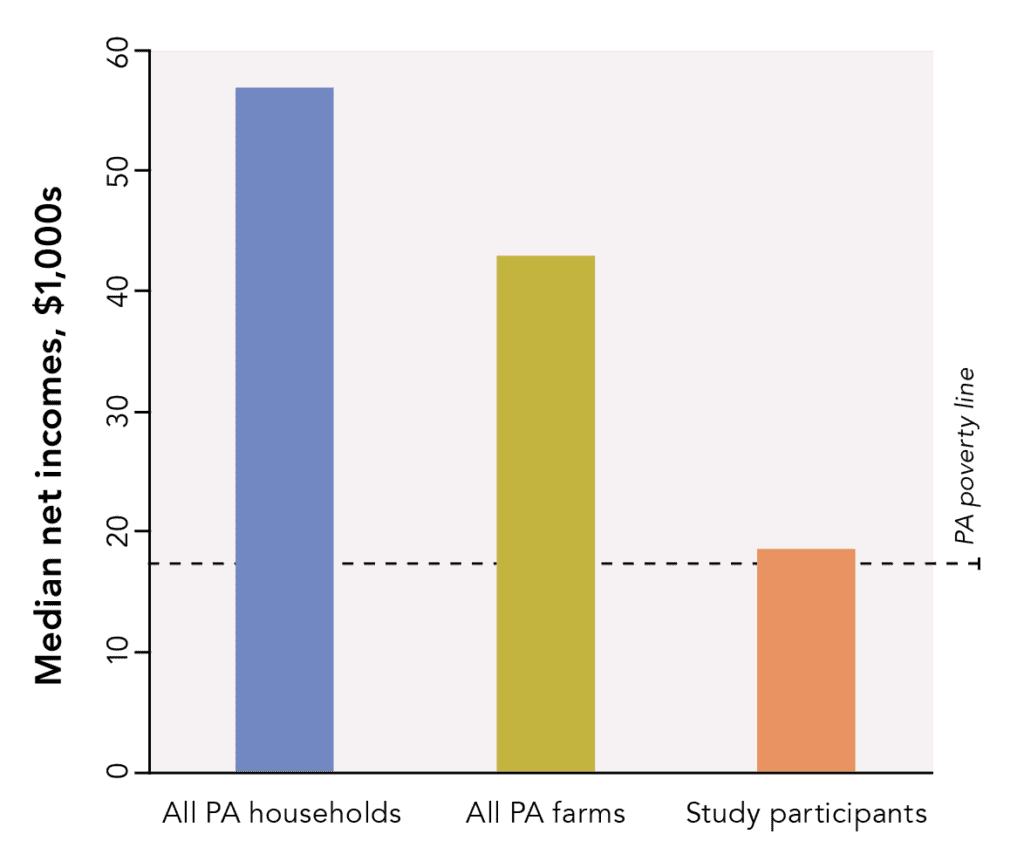

We found that the majority of direct-market vegetable farms were not earning a middle-class income. Participating farms had a median net income of $18,500, which approximates the 2020 poverty rate in Pennsylvania for a two-person household. Further, the net incomes of more than 70% of the farms in our study were less than half the median net income for all Pennsylvania farms, which include among others dairy, row crop, and wholesale vegetable operations.

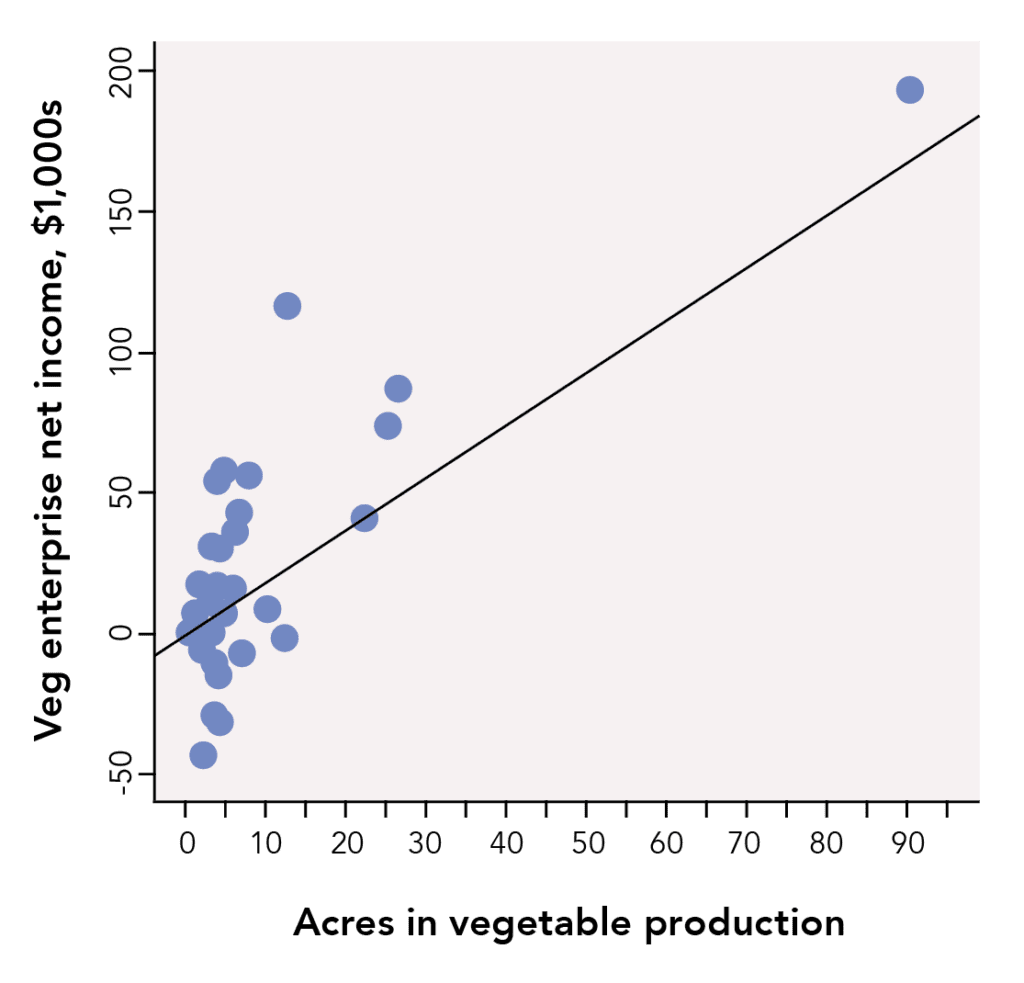

We did find some farms bucking the trend. A quarter of study participants had earned net incomes greater than the Pennsylvania median household annual income of $57,000. These farms tended to be larger in scale than many market-garden-style farms—typically, ten acres or more in vegetable production—and often capitalized on diversifying their revenue streams, with reselling products produced by other local farms proving to be one of the more profitable added enterprises.

Notably, however, many of the owners of these high-performing farms partially attributed their success to good fortune, such as access to especially lucrative markets or reliable farmland arrangements.

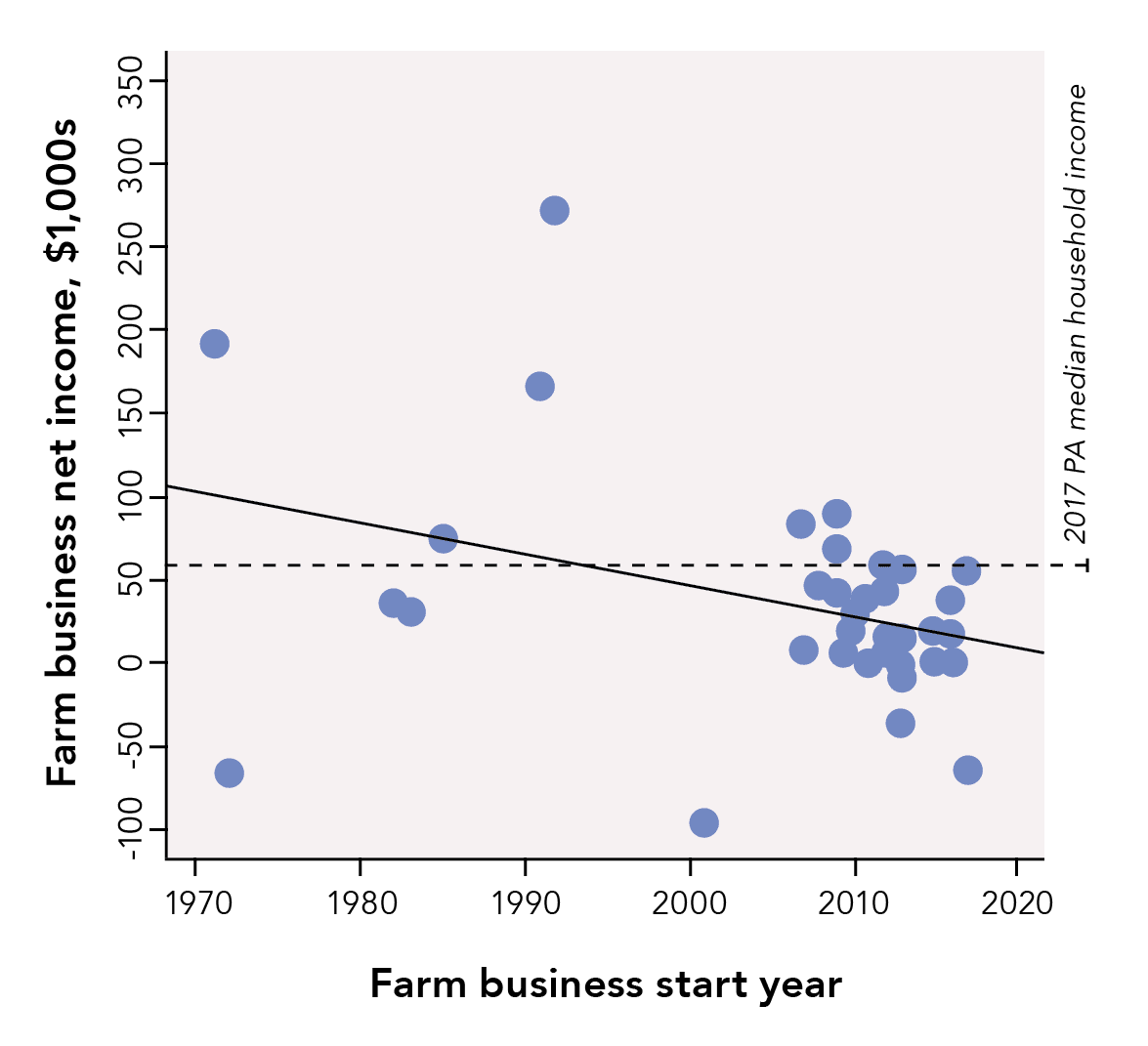

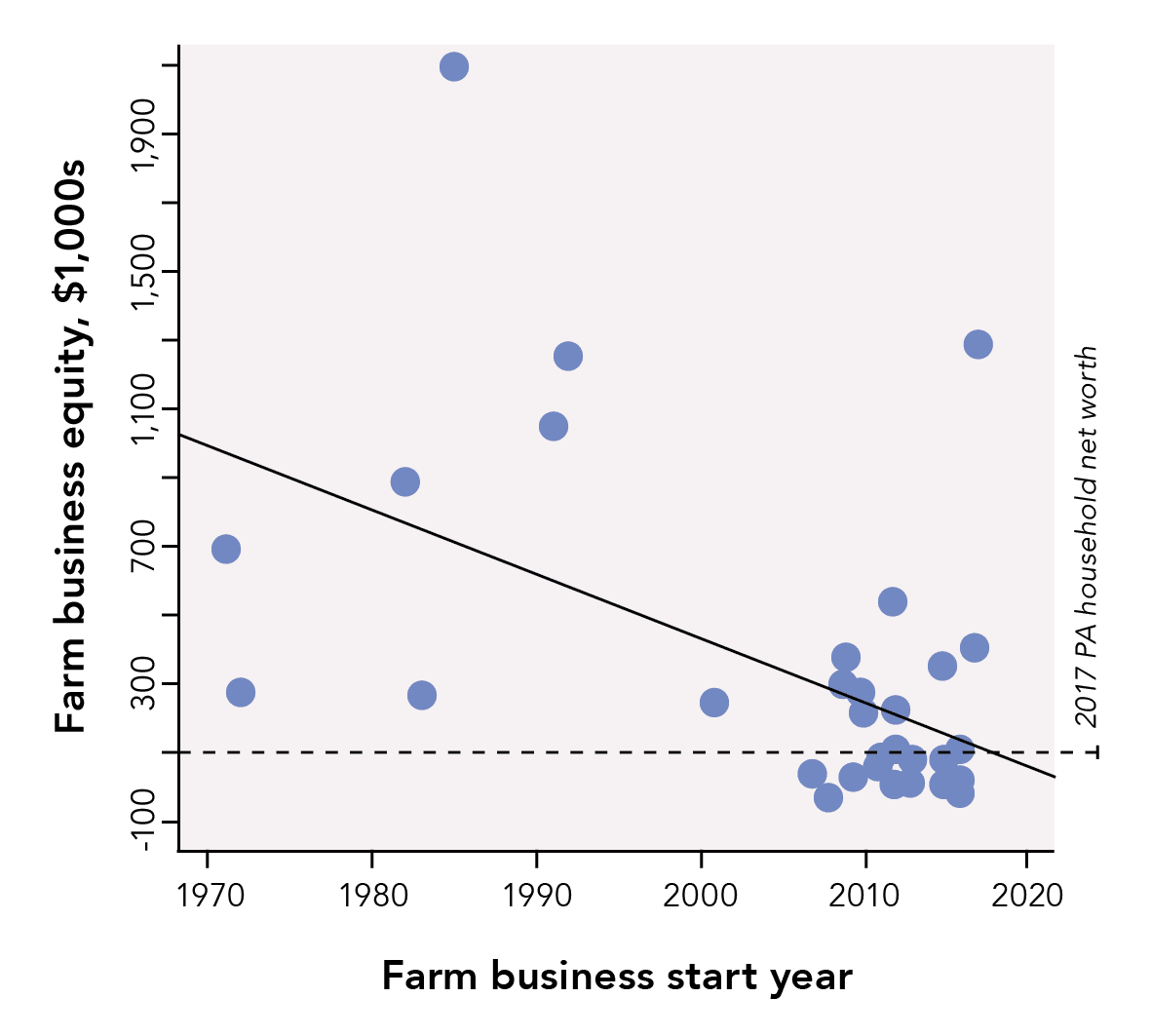

We also found that farms steadily increased income and equity over time, generally becoming more profitable the longer they were in business. Most farms’ net incomes exceeded the Pennsylvania median household income within 12 years of business, while accumulating equity in land, buildings, and equipment in the meantime.

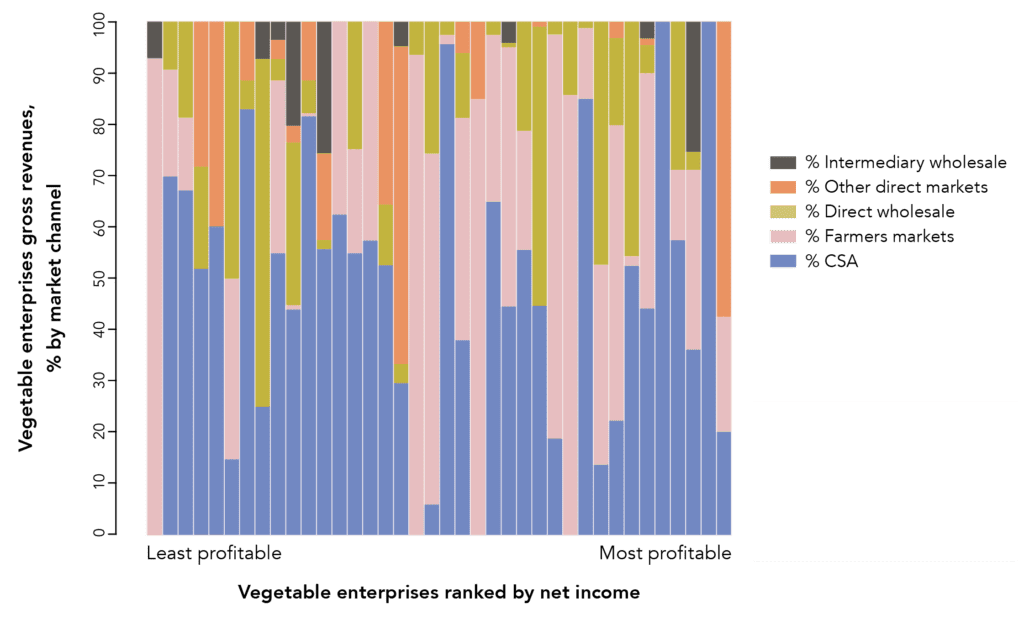

Interestingly, no single direct-market channel consistently outperformed all others. We found that all of the major sales channels utilized by farms in the study—farmers markets, CSAs, and direct wholesale—had a mix of higher and lower income cases. For farmers wondering whether or not to focus on selling their produce through particular direct-market channels, this finding indicates there isn’t a one-size-fits-all business model for financial success.

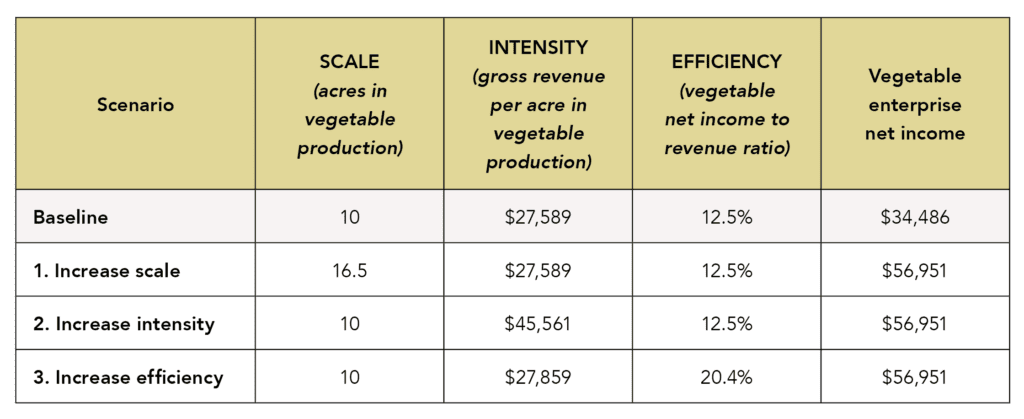

We identified three primary pathways for improving direct-market incomes: (1) increasing the number of acres in vegetable production; (2) growing more and higher-value crops per acre; and (3) developing more efficient production systems. Still, the land, labor, and capital needed to pursue these strategies may be out of reach for farmers who are operating at a loss or aren’t earning a living wage.

While all farmers want to operate profitable, self-sustaining businesses, the financial benchmarks identified by our study are consistent with industry structural challenges that negatively impact small- and medium-scale farms. Creating and expanding public and private programs and partnerships will be necessary to help direct-market vegetable farmers continue their essential work providing fresh, nutritious food for their communities.

These programs and partnerships should focus on equitably increasing farmland access, improving market opportunities, encouraging workforce development, reducing financial risk, and rewarding conservation best practices such as building soil health, protecting wildlife, and improving water quality.

Our financial benchmarking research is ongoing. Since compiling the findings detailed in our new report, we’ve partnered with peer organizations in New England (Community Involved in Sustainable Agriculture) and the Carolinas (Carolina Farm Stewardship Association) to expand the scope of our study to include data from vegetable farms located outside of the Mid-Atlantic region. We will also be analyzing the impact the coronavirus pandemic has had on study participants.

Read the full report: Financial Benchmarks for Direct-Market Vegetable Farms: 2021 Report

Our Financial Benchmarks Study was initially made possible with investments from Lady Moon Farms, the Jerry Brunetti family, the Shon Seeley family, and more than 120 private donors committed to strengthening local and regional food systems. Additional support was provided by a Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant and a Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture Research Grant.

If you are a direct-market vegetable farmer and are interested in joining this study, email us at research@pasafarming.org. Participating farms get custom financial benchmark reports and access to a learning community of their peers.